TERRAY (abbé Joseph-Marie), controller general of finances, born in Boen (Forez) in 1715, died on 18 February 1778. One of his uncles, a court physician under the Regency, made him study at Juilly and bought him a position as a clerical counsellor at the Parliament of Paris. Ordained a deacon, he led, it is said, a simple and austere life, entirely devoted to his palace work. Around 1753, he inherited his uncle's estate, left his mask of austerity, cynically shook off the yoke of ecclesiastical propriety and set an example of all kinds of scandals. He soon made himself known at the court of Louis XV, where corruption was a title of favour.

His servility to Madame de Pompadour earned him a rich abbey, and speculation in grain further increased his fortune. At the time of the general resignation of the parliamentarians in 1755, he was the only one who did not resign, became rapporteur to the court after the resumption of service, and played a fairly active role in the expulsion of the Jesuits, in concert with the minister Berryer, the abbé de Chauvelin and other creatures of the favourite. He completed the consolidation of his credit at court and won the favour of Louis XV by cooperating in the famous decree of the Council of 1764, which, under the pretext of free export of grain, starved France for the benefit of the royal agents and the agioteurs. He himself, as we have just said, earned immense sums in these shameful speculations on public misery. But the goal of his ambition, he did not bother to hide it, was the general control of finances.

By dint of intrigues, he was finally called to it in 1769, by the protection of the chancellor Maupeou, who announced his appointment to him in these cynical terms: "Abbé, the general control is vacant; it is a good place where there is money to be made; I want to make you give it. It is the account of an impartial and trustworthy contemporary, M. de Montyon (Particularités sur les ministres des finances célèbres, p. 154). His appointment gave rise to a thousand jibes, according to the custom of the French, who take revenge on their bad governments with good words. Thus it was jokingly said that the finances had to be very ill, since they were given a priest to "administer them. The finances were indeed in the most sad state, and since the dismissal of Machault

The finances were indeed in a very poor state, and since the dismissal of Machault the controllers general had followed one another without improving the situation. When Abbé Terray appeared on the scene, the people were exhausted, the Treasury was dry, the accounts were in disarray, and there was no credit. A man of expediency, unscrupulous and unprincipled, the new comptroller-general accepted this frightening office with great glee. He said cynically: "We can only pull France out of this crisis by bleeding her. He had no other financial theory than spoliation. He began with a series of special bankruptcies on rescriptions, a kind of Treasury bill, on assignations, on farm notes, on pensions, etc. Once he had taken this route, he began to take a series of bankruptcies.

Once he had started down this road, he did not stop, and his administration was nothing but a series of iniquitous and violent measures, of which we will mention only a few: the cutting off of half the arrears of matured annuities; the reduction of annuities (some by half); the forced borrowing of 28 millions from office holders; the increase in the bonds of certain civil servants; a tax of 6 millions on ennobled persons (who had already paid their titles in cash); sums demanded from the towns under various pretexts; the violation of judicial deposits by the substitution of depreciated values for consigned cash, etc. , etc.

Each week saw the appearance of new spoliatory edicts; and as they were usually issued on Wednesdays, Terray called them with insolent joviality his "mercurials." Moreover, he struck indifferently at all classes of society; he took from everywhere, from the farmers-general, from the State pensioners, from the trading companies, and even from the tontines where the artisans placed their meagre savings. In order to avoid any obstacles to his operations, and to quell all opposition, he took care to ensure certain financial advantages for the members of this body, a highly immoral means, but one which he knew from his own experience to be effective. Finally, he was completely rid of this control, which he had managed to render unobtrusive, when Chancellor Maupeou abolished the parliaments and replaced them with commissions. Terray, a creature of Maupeou, was one of the most active instruments of this coup d'autorité. It is well known what the salt tax was under the old monarchy, not only expensive beyond measure, but especially odious because of this legal provision which arbitrarily fixed what each family was obliged to consume, or in any case to buy from the king. Terray increased this tax by another fifth. He raised the price of a large number of tolls belonging to the king and even to the lords (forcing them to share the excess), seized part of the revenues of the University, held the bailiffs to ransom, created and sold new offices of brokers and stockbrokers, and even wigmakers, increased the duties on wine, wood, coal, paper, and books, and thus ruined several branches of commerce. Cynical in his words as in his actions, indifferent to good as to evil, insensitive to the clamours which arose against him, impassive before public hatred and contempt, armed with a sarcastic and wicked spirit, vicious and corrupt, with a cold head and a dry heart, greedy for the

He was one of those who contributed most to the degradation of the monarchy under the already shameful reign of Louis XV. Moreover, he was perfectly aware of the immorality of his role, and he expressed his contempt for himself and others crudely in words, some of which have been preserved. One day, the Archbishop of Narbonne representing to him that his operations were absolutely equivalent to the action of taking money from the pockets, he replied with calm effrontery: "Where do you want me to take it?" A playwright of our day, as is well known, used this impudently witty word in one of his comedies. Other words are also quoted from Abbé Terray, some of them very cynical, others of revolting harshness; for example, this reply to the head of a large family whom his edicts had ruined and who, in his just lamentations, said to him: "Must I cut my children's throats? - Perhaps you will do them a favour," replied the abbot. To others who reproached him for their ruin, he coldly advised them to go and work on the land or to enlist as soldiers.

One morning, it was noticed that the rue Vide-Gousset, so named because passers-by were often beaten and robbed there, had changed its name. The inscription bearing the name of the street had been scratched off, and in its place was written: Rue Terray. The Lieutenant of Police, de Sartines, was warned and went to inform the Controller General. The adventure is piquant and well worthy of Parisians," replied the Abbé Terray; "it is not in my country that these boorish Foréziens would have imagined such a malice... And are the Parisians amused by this? - There is a crowd on the Place des Victoires, everyone is laughing and applauding. - He continued, "Let them laugh for a moment; they are paying dearly enough. Few men have been hated, attacked, torn apart like him. Prose, verse, and caricature singled him out every day for public hatred and contempt, and the chorus of his victims was enough to curse and accuse him. Nowadays, a few rare writers have pleaded extenuating circumstances for him and have favourably assessed some of his measures, reductions on annuities, tontines, etc. But this paradoxical rehabilitation has not found any supporters. It is clear, in fact, that Abbé Terray's spoliatory expedients had none of the characteristics of economic reforms, good or bad; they were fiscal measures, and nothing more; he took everywhere, and in every way, he stole in the name of the State.

He took everywhere, and in every way, he stole in the name of the king," as has been said, in order to make himself indispensable to a greedy and constantly needy court, without forgetting himself, for he amassed a colossal fortune, the shameless display of which was a permanent insult to the public misery.

In 1770, he had revoked the edict of freedom of export of grain, and, as mentioned above, he earned enormous sums in hoarding operations in which the king was involved. His morals were very corrupt; surrounded by mistresses, he dispensed with paying them and allowed them to make the lucrative and scandalous traffic of graces and jobs. Three months after the accession of Louis XVI (1774), Abbé Terray was dismissed from the ministry and replaced by Turgot. The people of Paris expressed their joy in a tumultuous manner by dragging through the crossroads and burning the effigy of the odious minister, as well as that of Maupeou, who had fallen at the same time. Although burdened with the hatred and curses of the public, the ex-Controller General ended his days peacefully in Paris. He died

four years after his fall from power.

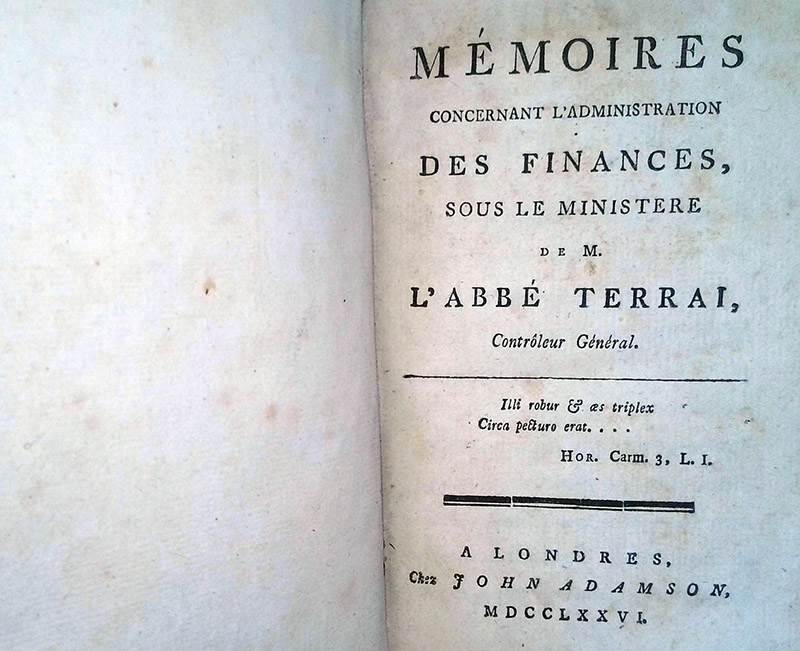

In London, in 1776, a memoir by Abbé Terray was published, written by a Sieur Coquereau, a lawyer. They contain interesting particularities.

Pierre LAROUSSE. Grand dictionnaire universel du XIXe siècle.

The above-mentioned work is available in our bookshop in a period binding